Roger Donne’s Miscellany |

|

|

About This Site |

Cycling |

Family History |

Contact Me |

Site Map |

Links |

HMS Exmouth – Life and Times of a Victorian Battleship

Construction

The Admiralty ordered the construction of HMS Exmouth on 12 March 1840, and the vessel was laid down to build on 13 September 1841 at Devonport. Originally, she was to be built to the design of Sir William Symonds for sail, as a two-decker, wooden-walled, 90 gun warship. William Symonds was one of the last of the Naval Surveyors who did not see a role for steam in any other than an auxiliary capacity. The Symonds design reflected his belief in the wide-beamed hull shape which provided the best performance in a pure sailing vessel.

Perhaps because of the uncertainty surrounding the future design of ships for the Royal Navy, the uncompleted ship lay on the stocks until 1852. Then, she was ordered to be converted to screw propulsion as of 30 October 1852. The conversion did not begin until 20 June 1853, and the ship was eventually launched on 12 July 1854. The fitting for screw was completed as of 17 February 1855. At this period, Devonport Dockyard, and particularly the Steam Yard at Keyham was well experienced in converting sail to steam. In the Yard, conversions were carried at this time on Algiers, Nile, Exmouth, Centurion, Aboukir, London, Lion, George, Royal William and Phoebe. The list, which is in date order of the commencement of the conversion, shows that Exmouth was amongst the first to be completed. Perhaps this accounts for the later deficiencies in sailing performance which were reported in contrast to say, Aboukir.

Conversion often involved a cutting asunder of the ship and the insertion of a machinery section. Ships conceived from the outset as a steam/sail combination abandoned Symonds wide-beamed concept in favour of a narrower-beam steam/sail combination. The increased length-to-beam ratio was found to provide better sailing off-wind. The new hull shapes had a poorer manoeuvrability and speed to windward, but this could be compensated by using the engines. Such lengthening did not occur in the conversion of Exmouth, with the steam plant being incorporated into the original hull shape as illustrated by the table of principal dimensions of the ship, which shows that the length is practically identical for both sail and steam designs. Such design compromises resulted in the later deficiencies in sailing qualities which noted and which led to the early retirement of the ship.

|

|

Length |

Breadth |

Depth in Hold |

Draught (launch) |

Draught (load) |

||

|

|

Fore |

Aft |

Fore |

Aft |

|||

|

Sail |

204ft |

165ft 11in |

23ft 8in |

|

|

|

|

|

Steam |

204ft 4in |

165ft 6¾ in |

23ft 8in |

15ft 6in |

20ft 6in |

23ft 6in |

26ft 3in |

|

|

Storage Spaces and Engine Space in Exmouth

|

|

|

|

|

|

Engine Space in the Lower Deck in Exmouth

|

The Steam Plant

The engines of 400HP were supplied by Messrs Maudslay Son and Field, and were placed on board in 1854, who also supplied the tubular boilers. The engines comprised two horizontal, direct acting cylinders, each 64 inches in diameter with a 3ft stroke. The engines weighed 105 tons, with the boilers weighing another 104 tons to which would be added another 56 tons of water when full.

The boilers were heated by 12 furnaces in one stoke hold. Ventilation was provided by pipes with hoods. A single telescopic funnel 6ft in diameter and of total length 54ft was lowered when the engines were not in use so as not to impede the sails (the main mast was 50ft abaft of this funnel). When not in use for propulsion, the boilers were still used to operate the distilling apparatus, manufactured by Grants, for the distillation of sea water.

The manufacturer Maudslay Son and Field was a based in Lambeth. In order to transport the engine parts to Devonport, the paddler, HMS Rhadamanthus, was used for the journey from Woolwich Yard, where the engines were delivered, to the Dockyard at Devonport. The ‘Times’ naval and military intelligence column reports on 12 April 1854 that the boilers are being delivered by Rhadamanthus and later, on 23 August 1854 that Rhadamanthus is collecting machinery from Woowich for delivery to Exmouth at Devonport.

The screw propeller was 17 feet in diameter and the total weight of the gear was 42 tons. The propeller was provided with a T-head and clutch for its disconnection when not required. The whole propeller could be hoisted to prevent drag.

Armament

At launch the armament fitted is as shown in this table:

|

Deck |

Number of Guns |

Type |

Weight |

Length |

|

On Lower Deck |

32 |

32 Pdrs |

55 cwt |

9 ft 0 in |

|

On Main Deck |

32 |

32 Pdrs |

56 cwt |

9 ft 6 in |

|

On Quarter Deck |

18 |

32 Pdrs |

42 cwt |

8 ft 0 in |

|

On Forecastle |

8 |

32 Pdrs |

42 cwt |

8 ft 0 in |

|

One of the comments recorded in the ship’s record is that “As is frequently the case, many of the Q’ Deck guns are of little use, the Rigging preventing their being brought to bear on the Target when a little before or abaft the beam”.

In a report of 30 Sep 1862, at Devonport, “in consequence of the contracted state of the Quarters”, Capt Paynter recommended the armament to be : Upper Deck 2 x 110 pdrs Armstrong and 8 x 40 pdrs Armstrong Main Deck 14 x 40 pdrs Armstrong Lower Deck 16 x 40 pdrs Armstrong Although not strictly comparable in the weight of the armament, an impression of a gun deck mess can be obtained from the photograph opposite which shows a 68 pdr Armstrong muzzle loaded gun taken aboard the restored HMS Warrior in Portsmouth Dockyard. |

|

Baltic Service in the Crimean War

Captain Hon. Frederick T. Pelham was appointed to command Exmouth in November 1854 and after working up she sailed for the Baltic to support operations against Russian ports and coastal defences on15 Mar 1855. In July, Exmouth in company with Blenheim and two gun-boats reconnoitred the river Narva, and went into action against a small fort at the mouth of the river. While in the Baltic, she became the flag ship of Rear Admiral Seymour in the blockade of Cronstadt in August 1855.

The Baltic operations were notable for the first deployment of a new naval weapon by the Russians – the mine, described as an ‘infernal machine’ by the war correspondents of the time. Rear Admiral Seymour had a personal encounter with one of these weapons and a lucky escape when the detonator from a recovered mine blew up in his face while he was examining the device on the poop of Exmouth, causing temporary damage to his eyes. To counter these new devices, a rudimentary form of mine sweeping was devised using a rope towed between two boats.

Exmouth returned to home waters in November 1855. However, at very short notice she was ordered up from Plymouth at the beginning of December to attend a naval review in honour of the visit of the King of Sardinia; the ship was coaled in record time, and cleaned all over, to sail to Spithead. Finally the crew got their leave on 10 December 1855, when the ship finally had finished its duties in the review.

An Unfortunate Cruise to Portugal

After refurbishment at Devonport, the ship sailed for Lisbon on 22 Oct 1856. This voyage was unfortunate in that there is the first record of the ship grounding. A report dated 31 Dec 1856 records that ship struck ground while at anchor on 2 November 1856 at Lisbon after “Pilot left ship, consequence of the falling tide”. As if that there not enough misfortune, a further report dated 20 June 1857 records that ship grounded off the Land’s End on 12 May 1857, in Whitesand Bay, presumably when returning to Devonport.

The latter incident caused serious damage to the ship’s bottom and occasioned major repairs at Devonport and, according to a report in 'The Times' of 22 May 1857, Captain H Eyres, C.B. and the master, Mr. Cavell, were tried by court-martial convened on the flag-ship Victory in Portsmouth harbour for 'getting the ship ashore...near the Lizard'. To facilitate repairs to the hull after this grounding, the boilers were removed. Their reinstatement and refitting of the ship for sea provided an interlude during which the ship remained moored in the Hamoaze, with occasional excursions to test the engines. Finally, a trip along the coast to Portland provided confidence that the ship and its power plant were sufficiently reliable for its next major cruise.

The Mediterranean Cruise

The story of the Mediterranean cruise is told in extracts from the ship’s log (see James Donne’s Naval Record). The cruise lasted from 16 June 1859, when the ship set sail from Devonport, to 3 October 1862, when it returned to Devonport and was paid off. During that time, the ports visited by the ship included Valetta, Naples, Palermo, Corfu, Zante, Cephalonia, Messina and Piraeus. In October 1861, Exmouth practised steam evolutions with other ships of the Mediterranean fleet in Naples Bay. The log shows that the steam plant was still unreliable, with faults developing after an hour or so under steam. Clearly the engineers were hard-pressed to keep the plant functioning. A major refurbishment of the boilers and steam plant was carried out at Malta in February 1861.

|

This fine painting shows the British fleet in Naples Bay, with HMS EXMOUTH on the right in the foreground and HMS MARLBOROUGH to the left. It is reproduced by kind permission of Commander Richard Davey RN Ret'd, whose ancestor, Captain Paynter, commanded the EXMOUTH at this time. |

“Useless”

During the Mediterranean cruise, the captain (Captain Paynter) was asked to report on the sailing qualities of the ship, which were clearly found to be unsatisfactory. Captain Paynter gives a comprehensive report contained in a letter which is bound into the ship’s books. He states that he considers her to be a vessel of indifferent speed and provides a list of examples under various wind speeds and directions. The indifferent performance he ascribes to the length to breadth ratio of 3.3 to 1 and the angle of the bows which produces a high drag. The performance under steam was also found wanting, in this case Captain Paynter points to the specification of the engine, which at 400 HP he considers to be underpowered, compared to similar ships in which steam plant of 600 HP fitted. However, Captain Paynter considered Exmouth to be a strong and well-built ship, which could become an excellent ship if she were lengthened by 50 feet.

After return from Malta and at Devonport, Exmouth was placed in 3rd Division Steam Reserve in accordance with Admiralty Order dated 27 Sep 1862 while her future was considered. A letter to Devonport dated 17 Mar 1863 states that the “ship is too slow under steam for efficiency” and the Sick Bay is very small and inconvenient”. A later memorandum dated 16 Nov 1863 states that she was “considered as useless” but “might replace worn out Coast Guard Ships” and in accordance with an order dated 29 Jun 1868, she was transferred to 4th Division Steam Reserve.

A Long Decline

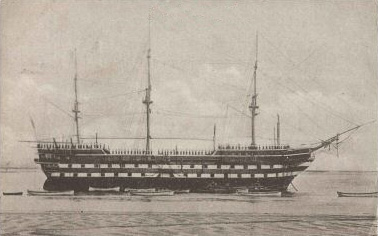

|

Training Ship "Exmouth" moored at Grays, Essex |

After some service as a guard ship at Plymouth, the end of Exmouth’s naval career came in 1876 when an order of 15 May 1876 instructed that the machinery was to be broken up as opportunities offer. The old boiler was removed in May 1876 and the crank shaft and propeller shafting sold in November 1877. This was not however the end of Exmouth’s useful life though. From 1877 to 1878 she was refitted at Devonport for use as a training ship for the Managers of the Metropolitan Asylum District, to replace a similar ship Goliath which had been burnt. After refitting, Exmouth was towed to the Thames and moored off Grays in Essex.

|

The End

Exmouth continued to provide a home for pauper boys for many years until time began to take its toll. After 25 years of service as a training ship, Exmouth eventually became too dilapidated for further use. In 1903 her hull was found to be defective and she was sold for scrap in 1905. However, that was not quite the end of the Exmouth story, because a replacement training ship was ordered, a replica of the old Exmouth in steel, which continued in service until 1939.

©Roger Donne 2005-2010

Updated 12 November 2010